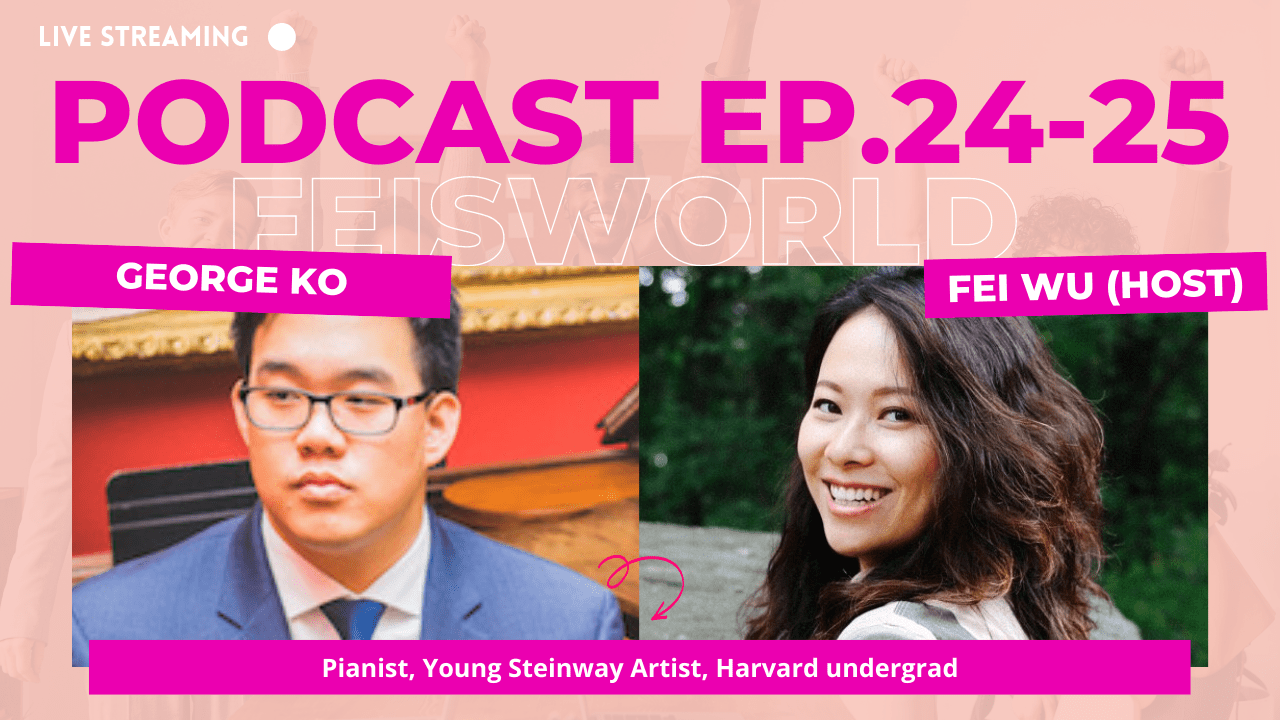

George Ko: Pianist, Young Steinway Artist, Harvard Undergrad (#24-25)

Our Guest Today: George Ko

George Ko was Introduced by Barry Alexander, a wonderful guest from an earlier episode on the Feisworld podcast. George Ko joined me in a 2-Part interview. I had so much fun chatting with George at a piano recording studio inside Harvard University. We met for the first time during the interview but somehow it felt like we’d known each other for 20 years.

“Growing up in the Asian community, people are obsessed with Ivy League schools. All the successful people I’ve met, Harvardian or not, succeed because of the people they are, not because of the schools they went to.” – George Ko

George had an unusual path to becoming a successful pianist. As a young boy, his mom refused to prescribe medication for his severe case of ADHD and instead invited a piano teacher to their home. At the beginning, George struggled to sit still and play for even just 5 mins.

Today, more than a decade later, George earned the title of Young Steinway Artist, appeared with Harvard’s prestigious River Charles Ensemble, performed at Carnegie Hall more than half a dozen times, as well as Steinway Hall that led one critic to proclaim “a rising star if ever there was one.”

To my surprise, George never planned on becoming a pianist. He thought playing the piano would just be a hobby on the side. He majors in Music at Harvard and founded 4 startups during freshman and half of sophomore year.

“My father was an entrepreneur and I was able to learn a lot from him. At age 5, he gave me my first briefcase, At age 8, I made my first hotel reservation. At age 10, I made my first sales call. At age 12, I became my father’s temporary accountant.” – George Ko

George found himself feeling depressed during the second half of his sophomore year at Harvard. He didn’t know why. Then he heard Benjamin Zanders conduct the 4th Brahms Symphony, he knew right way that he had to be a musician, either a pianist or a conductor.

When George finished sophomore year, he convinced his parents to make a very unconventional Chinese-American decision: George wanted to take a year off so he could study piano under John and Mina Perry, who taught George the professional side of being a pianist. The wonderful learning environment was fostered by St. Margret’s School, where George attended from pre-school through high school. At the end of the year, St Margret’s invited George to showcase his work at a solo recital in front of hundreds of students.

“During my year off, I always questioned myself:’Am I doing the right thing? Is this the right path for me?’ A the same time, I was bombarded by internship offers from LinkedIn and Google. I had to turn them down. People asked me why I would do that and how I could survive in the competitive field (music).” – George Ko

The most important lesson George learned in his magical year off was: You have to stop comparing, and start connecting with people. Work is important, but time with people is also important. This observation, in turn, enabled George to become a much better musician.

“The view for classical music today is that you have to be hyper virtuosic. There’s a specific set of rules for how you should play. But people forget that music is organic, and music is an expression of the human soul (as cliche as it sounds).” – George Ko

Given the path George had chosen, I was intrigued to ask if he had to face any challenges, rejection from family and friends, specifically as a Chinese-American. Perhaps his struggle and wisdom will aid many of us Asian-Americans in the pursuit of our dreams.

“One thing I am very passionate about is the Asian American culture. As a child, I visited the Chinese American Museum. My father helped found the Irvine Chinese School I went to, and he is also a member of the Community 100, which is an organization for leading Chinese Americans in the US. He supported candidates to get into office, such as Ted Lieu and Judy Chu. Judy is the first Chinese American congresswoman.”

“Only a scholar deserves the highest regards in society” is an old Chinese saying. It can be inspiring but the path of getting one there is questionable in this day and age. As an Asian American, you have to represent your culture, educate other people about your culture, and you have to be willing to step out of your comfort zone to fight to be heard.

Growing up, many Asians and Asian Americans are taught to be restrained. We are conditioned to exercise our mental control over our emotions. We don’t attack, we reflect.

“It is our duty to show people our culture. Being part of this ethnic group is part of being American. America is a melting pot – we are group of people forming this wonderful fabric of culture and experience that supports one another.” – George Ko

For George, the importance of playing music isn’t about never making mistakes (everyone, including the top performers, make mistakes!). Instead, it is about creating an experience that reminds the audience of something important in their lives, or inspires them in some way. The audience is not only enjoying music as entertainment but as a moment of reflection.

“I never change the way I play”. – George Ko

An older Polish woman walked up to George after his concert in Italy and said to him:”the way you played reminded me of my time during the World War II”. That was all she said. But to George, the message was more important than any applause he could have hoped for.

“My job is not just to provide a source of entertainment but to touch people. My role model is Yo-yo Ma, who received many criticisms. He may not have the best techniques, but listening to him makes you look inside yourself. ” – George Ko

I believe that people like George have obligations to share their skills with the world, to touch people in ways they didn’t think they could. These specialized skills come at a cost – that is to practice relentlessly, to learn from everyone and follow no one, to tune out the chaos from the world (the criticism, judgement and rejection), and eventually to hear the calling beyond themselves for the good of the people.

In Part 2 of my interview with George, he talks about the business side of things. After founding 4 startups in just 1.5 years at Harvard, I figured that George must have a “secret set of skills”, aha moments that contributed to his success. George built his website including writing and photography in one week (hint: very little technical skills are required and anyone can learn how to do it!). I was also surprised to find out that someone as young as George, already has a clear vision of where his journey is going to take him, and what he really hopes to accomplish. It is not as simple as just being a successful musician himself. It is rather a universal message that’s going to change music and music education around the world.

During George’s year off, he had the pleasure to conduct a youth orchestra in Orange County, California, where he’s from. He quickly realized that it’s not because pop music is better or easier to consume, it’s because we never gave it a chance.

“If I could somehow, in my life, help bring these (classical music) programs back, give people a chance, or at least open the cover of this wonderful book, that will be the ultimate goal of my career.”

George Ko

To learn more about George Ko, please check out his website, follow and connect with him via Facebook and Twitter,

Do you enjoy this podcast? If so, please leave your comment below and share the podcast with your family and friends. Your support will keep me on track and bring many other unsung heroes to this podcast.

iTunes feed and subscription Non-iTunes RSS feed

George Ko is currently practicing:

- Beethoven Sonata Op. 7

Chopin Etude Op. 10 No. 3, 4, 5, 6

- Chopin Nocturne Op. 48 in C Minor

- Ravel Tombeau de Couperin

Repertoire currently using to perform:

- Beethoven Sonata Op. 54

- Chopin Etudes Op. 10 No. 1, 2; Chopin Etudes Op. 25 No. 3, 4, 5

- Chopin Concerto No. 1 in E Minor

- Chopin Ballade No. 3

- Chopin Scherzo No. 3

- Debussy Sutie Bergamasque

Transcript

Part 1

The Life Of A Pianist, Young Steinway Artist, Harvard Undergrad (Part 1) with George Ko – powered by Happy Scribe

Welcome to the Feisworld podcast, engaging conversations that cross the boundaries between business, art and the digital world.

Introduced by Barry Alexander, a wonderful guest from an earlier episode on the Face World podcast, george Co joined me in episode 24 and 25. This is part one of our conversation. George is going to perform at the faculty room at Harvard on Thursday, February 19, 2015. I had so much fun recording this interview with George at a piano practice studio at Harvard. We met for the first time during this interview, but strangely, it felt like we had known each other for 20 years. My favorite part is probably having George play along during the interview while he was giving examples or telling a story. There were more than just sound effects, but rather they were perfectly integrated into our conversation. At 22, so far the youngest guest on my show, George, is a pianist, young Steinway artist and an undergrad at Harvard. He says that growing up in the Asian community, which I totally agree, people are generally obsessed with Ivy League schools. As an adult, he quickly learned that successful people succeeded because of the people they are, not because of the schools they went to. By the way, you will also be surprised by how he got into Harvard, and perhaps you should advise someone else to apply to.

George had an unusual path to becoming a successful pianist. As a young boy, his mom refused to prescribe medication for his ADHD and instead invited a piano teacher to their home. Today, more than a decade later, George earned the title of a young Sinewy artist, appeared with Harvard’s prestigious River Charles Ensemble, the Carnegie Hall for more than a half dozen times, and Steinway Hall, which led one critic to proclaim a rising star if ever there was one. He majored in economics at Harvard and founded four startups in the first year and a half before he dropped out for one year to dedicate to piano practice. He shares his joy and struggles during that magical year. What’s the purpose of playing music? For George? He says that it’s about creating an experience that reminds the audience of something important in their lives or inspired in some way. They’re not only enjoying music as entertainment, but a piece of reflection. He also talked about being Chinese or AsianAmerican and his obligation as a musician and a friend. George believes that it is our duty to show people our culture. Being part of this ethnic group is part of being American.

America is a melting pot. We are a group of people forming this wonderful fabric of culture and experience that supports one another. Thank you for letting me share this wonderful story with you. For additional tools and resources, please visit my website, F-E-I-S-W-O-R-L-D. Without further ado, please welcome George Coe.

So I’m here with George. How do you pronounce your last name? Correctly?

Co co.

Okay, that’s not bad. You got to show me how you write it in Chinese. Do you write in Chinese?

About 60%. It’s okay. It’s not fantastic. I wish I could write more fluently, but at least I can speak it fluently. If at any point you want to switch to Mandarin and test our listeners Chinese, that’d be fine.

Awesome. Do you speak Mandarin at home, by chance?

Yes, actually, I’m the first generation born in my family. My father and mother grew up in Taiwan, and they moved to this country. And I lived with my grandmother, and she doesn’t speak very good English, so my parents made it a requirement that once you’re in the home, you must speak Mandarin.

Wow.

So my brother, his sister and I, we grew up speaking Mandarin. And so whenever we go back to Asia, we’re very comfortable. Reading and writing, though, is a little bit of a challenge.

I can imagine all of you guys are born and raised here.

In California, but nice.

So you’re originally from California, and what brought you here seems to be Harvard, which is not a bad option. How did you select your colleges? Not so long ago, I guess.

Well, the funny thing about colleges is actually my first choice was not Harvard University, it was Columbia University. I have a train program with Juilliard, but most importantly, it’s in New York City. And I love New York. And since 8th grade, I was determined to go to Columbia. I had all the blue packets and the Columbia flag on my desk.

Why is that?

And I just fell in love with the school. My friend, she actually went to Barnard, and she took me to a class at Columbia and just loved the environment. And so I was very determined. But funny thing was, I applied early decision, and I got deferred, and I felt that, okay, maybe I didn’t get in. And then I was rejected from Juilliard, and then that was upsetting. But then the funny thing is so the last Wednesday of every March, the colleges released all their decisions, national Decision Day. And I received an email from Stanford, University of Pennsylvania, wharton, Columbia, Yale, Princeton, Brown. And they all rejected me. Unanimous.

You’re kidding me.

No. And I was very disappointed. But it’s all right. I still got into some schools and still fortunate to go to college. So I said, It’s a little upsetting, but it’s fine. They probably have too many Asian people. No schools anyways.

That’s right.

And then I was walking to class, and on my back then iPhone four and still old phone, and I got a notification from Harvard University. So I checked the email, and I was expecting another rejection. The first three words I wrote were, we are delighted. And then I read the next two sentences, and I was so excited, I ran around the whole school.

Oh, my goodness.

And it’s funny that I got into harvard because I actually applied as a joke. I didn’t think I could get in. And I applied to Harvard University at 11:59 p.m., december 31. This is the last minute possible. I mean, it was due January 1, but at that 12:00 a.m. Mark. And my high school historically would only accept one. Usually one student would go to Harvard, and that one student in my class got in in 7th grade.

I will say that story for another episode.

So I thought that there was no chance. But yeah, I applied. And I asked my mom, should I just check the box on the common application? She said, why not? I mean, it doesn’t hurt. So thank God I checked that checkbox.

Because this was the last school possible for you. Did you get rejected by all the other schools here?

No. So I was very lucky. I was accepted into Ross School of Business at Umich. I was accepted at the Stern School of Business at NYU, and I was also accepted as a trustee scholar at USC for the film school and the business school. So I was very fortunate. So even if I didn’t get into Harvard, I would still be very happy. It just was a little nice icing on the cake.

Wow, I had no idea. I mean, we only caught up for half an hour on the phone prior to this. But isn’t life interesting? Sometimes it is where your journey takes you, right? As I mentioned yesterday, I was at a bridal shower earlier. Not really my forte, I didn’t know what to wear. And the funny thing is, we had this simple game, and there were 40, 50 women at the party, and you’re supposed to answer these 25 questions, and you fold your paper and drop it into the box. And then in the end, I guess, one of the maids said, faith, did you turn your paper? I said, oh, I totally forgot. She looked at my paper, she said, There are three questions you didn’t answer. And it was really embarrassing. I was looking around and she said, she filled them out for me just as a joke. And then the bride took one out of the hat, and it was me who won the first game. So I think it’s just really, really funny. But I think the Harvard reward is much more significant.

I’m very fortunate. As an Asian American, I grew up in that community where people were obsessed with the Ivy League and say that’s the goal of life, to go to these schools. But to be honest, it’s a wonderful opportunity, don’t get me wrong, but it’s not the end goal. I mean, every serious professional I’ve ever met, Harvardian or not, was successful because of the person that they are, has nothing to do with the institution. Just so happens that Harvard selects candidates that have similar roles to those who do succeed in the professional world. So I’m very fortunate but if I didn’t get in, I think I would still be the same person as I am today.

Yeah, five minutes in. I think you will be. You are only 20 years old.

I’m 22.

22. Good for you. Your wife is beyond your years.

You’re very kind.

I’m sure some people would say that. Oh, because you’re at Harvard, so you don’t care. I’m sure you hear that sometimes, but it is true when you look around that there are a lot of dropouts from Harvard. You could argue they’re very qualified, very smart, even before they got in. But it’s really true. Now in 2015, I look around my friends, people are really influential in the world, and clearly not all of them graduate from Harvard or any of the other IDE League schools. So it’s interesting. I’m just so glad to have you on my show, to be honest, and Asian American, and especially in the past 1510, 15 years, there are just so many success stories, and we share our voice. It’s not just Chinese Americans, but also Vietnamese and Thai, and it’s a blossoming society community, and it’s incredible. So you’re on my show because you’re a very successful, I think, piano player and was referred to me by Barry Alexander from an earlier episode of my podcast. And we both adore Mr. Alexander. And tell us about your piano career. You have thousands of fans on Facebook. I see you travel all around the world.

So tell us what it’s like to be you.

Well, maybe we should start from the beginning of how I started playing piano. When I was young, I was diagnosed with a very serious case of ADHD, and my mother went to the doctor, and the doctor said, well, you know this crazy kid, you probably need to give him some pills. But my mother refused. She didn’t want to give drugs to a three or four year old boy. So she used to play piano, and she remembered it was art that required a lot of discipline. So she said to me, okay, I’m going to give you piano lessons. And the first piano lesson I had lasted five minutes. I could not sit on the bench. I just run around and try to get away. But my mom was very persistent, and I was very lucky. The teacher that I had, March Chen, she did not give up. She would say, I’m at least going to get this kid to play ten minutes on the piano before he starts running around. And it took a long time, and I finally was able to focus on one task, and that’s how I got into piano. But at the same time, I hated classical music.

It despised the same as a three year old. I forgive you.

Yeah. I mean, I wasn’t like Mozart, going to concerts and being happy, but my mother did bring me to concerts when I was three. Then the county where I grew up in Orange County, they have this wonderful symphony, Pacific Symphony, and they would have these afternoon concerts for kids, just for kids. And I went to those concerts starting when I was three, and I listened to most her symphonies Berlios, Beethoven, Shasta, Kovich. But I still hated all of it. And it wasn’t until when I was 13, my mom this is when Lenglong, the famous Chinese fantasy, just had this huge spur of fame. And my mother got tickets in San Diego and we arrived late at the concert. I really didn’t want to go. I wanted to go play Pokemon in the car. And we weren’t allowed to inside because we arrived late. My mom begged the doorman, look, we drove 4 hours here because of traffic. I bought these tickets a year ago. Can I at least let my son go listen? Because he plays the piano. And doing isn’t fine, but you just have to be quiet. So my mom pushed me through the doors and walked into the hall.

And then I heard the most beautiful thing in the world. And I was stunned. I was supposed to sit in row F, but I just stood in the aisle and I didn’t move. I was stunned by the music. And I’ll never forget it was the second movement of Wach Mana’s Second Piano Concerto. And that’s when I first really started appreciating classical music. And that’s when I started to gain interest, to play the piano. But never had I thought I’d be a concert pianist or a pianist of any nature. I was still very heavily focused on my entrepreneurial pursuits.

Nice.

When I was growing up, my father, he’s an entrepreneur, and when I was five years old, he gave me my first briefcase. When I was eight years old, I made my first hotel reservation.

Wow.

When I was ten years old, I made my first sales call. When I was twelve. I was his temporary accountant. I just want to clarify, these don’t violate any child labor laws. But, you know, I learned a lot from him. And I did business in China. I looked at manufacturing in the Guangdong province. So I was very interested in business and which is why, as I mentioned earlier, all the schools I applied to were mainly business focused. I never thought I’d be a pianist. I just thought it’d be a thing I’d do for fun on the side. And so, coming to Harvard, I was an economics major and I founded four startups, and two of them did quite well. The other two not so much.

Since you started Harvard?

Since I started at Harvard. And I did that in the span of my freshman year and half of my sophomore year. And during my sophomore year, I was extremely depressed and not happy with myself. I didn’t know why. I thought what I did was what I love. And it’s funny how life throws these special moments and these interesting turning points. In the fall of my sophomore year, I was sitting in Sanders Theater at Harvard, and the Boston Philharmonic game gave a concert. Ben Sander conducted the Fourth Brown Symphony. And for some reason, after I heard that symphony, I knew from that moment I have to be a musician, either a pianist, or if I can’t make it as a pianist, at least a conductor. And I said, I have to give up. I have to give up my entrepreneurial endeavors. So I hung that coat up, and when I finished my sophomore year, I asked my parents to do a very unconventional Chinese American thing, which is, can I take a year off to study piano? Because I’ve never really studied piano seriously my whole life. I just play 1 hour a week and play in the talent show.

And they had a considerable thought, and I’m very lucky. I have very considerate parents, and they said, Fine, we’ll support you, and we’ll help you with this one year and to cultivate your skills. And so that’s what I did for a year, was to learn how to practice the piano just like a five year old. Again, learning to play the piano, but how to play, to be a professional. And it was very hard. But now I’m very thankful with the teachers that helped me, john and Mina Perry, they had a lot of patience to teach me professional work at the piano, and from that, it led to where I am now. So that’s kind of a quick story.

That’s a great journey in a nutshell. And wow, you know, sometimes I feel like I ask the next question too fast, and that story in just a few minutes kind of triggered a lot of different ideas. And by the time that you realized you wanted to be a musician, that must have been age 2021.

That was when I was 2020.

Wow, age 20 is very interesting. I happened to have a cousin and a very close family friend who are just that age, and it’s a difficult age to be. And I’m very glad that I feel like your audience kind of span across a pretty different age range. But I want people in college to kind of listen to this, because when I look back when I was 20, I was very anxious, and I was even more anxious that I had to hide that feeling for the longest time, and you’re not too far from that. But tell me about that moment and that year. It was a magical year for you that you left Harvard, and did you live in California? Did you stay in Cambridge?

So my parents were very kind to house me for the year. I actually studied with Mina Perry when I was in California, and she really, you know, helped me continue my interest in piano and develop a really good foundation. And so I just thought naturally I would study with her and her husband for the year off. So I stayed in California mostly. But surprisingly, my musical education for that year was fostered by my high school, the high school that I attended. So I attended a small private school called St. Margaret’s from preschool through 12th grade. And I’ve been at that school for 16 years.

Oh, man.

And at that time, they built a brand new concert, a performing arts center, and they have a 450 C concert hall, and they asked me to help them select a piano. So I went to the Factorynstein Way, and I helped selected their piano. But they actually were very supportive of my year off. They would welcome me back to give talks, play with some of their groups, and then at the end of the year, I played a solar recital at the hall to showcase the work I did for my year off. So, yeah, there’s a lot of different factors that help support that. I guess in terms of the struggle, I think we all feel this, despite where we’re at, especially at a young age, we like to compare. We like to say, oh, that person is better than me. How can I be better than them? Well, when I started my year off, I’ve been to a lot of piano festivals, and I’ve listened to these 13 year old girls play. I mean, pieces of ridiculous caliber. I mean, like pieces like yeah.

I.

Mean, like someone who is 20 would try to do that 30, 40 years ago. But I mean, there’s 13 year old girls that play that the show can eat, who’s like, it’s nothing. And so I always question myself, is this the right path? Am I doing the right thing? And at the same time, I was being very fortunately bombarded with internship opportunities at LinkedIn, at Google. I would turn them down because I’m so determined to be a musician. And people would question people question you. Why would you do that? And I would ask myself that same question, why would I do that? I mean, these are opportunities people would die for. You know, it’s so hard to get a job, especially now, because of the rise of accessibility to education. I mean, everyone’s resumes are incredible. So how do you survive in such a competitive field? And so these are all questions that happened during the year off. And the most important thing I learned, at least, was you have to stop comparing, and you have to start connecting with people. You have to get help when you need help. And don’t be afraid to ask for help and not forget what’s the most important thing in life?

And aside from religion, if we keep the spirituality aspect out of it, the most important thing in life is people. Because once you die, all your accomplishments are gone. But the relationships you had were probably the most treasurable things. And so my year off, really, folks told me your work is important, but your time with people is important. And for me it was a good time to reconnect with my family and my friends. And in that way I learned what music can really do. There’s this hyperpopularized view of classical music today, at least in the classical field, where it has to be hyper virtuosic. You have to win this competition. There’s a very specific set of rules of how to play the piano. But we forget music is organic. It’s an expression of the human soul, as cliche as it sounds. We call it a universal language. And it’s universal because you don’t need to speak it to understand it. But if we play like robots and conform ourselves to this system, then we’re not playing music anymore. It’s just a really nice, clean recording. And so I think, had it not been for my journey through understanding people during my year off, I don’t think my music could have gotten any better or I could have understood the piano even more.

That’s some deep thinking there. This is incredible because I released 19 episodes of my package working in the 20th one so far I’ve interviewed two musicians. One is Bare Alexander and the other is Ralph Peterson, Jr. Who is in his early fifty s and has been playing drums his whole life, also plays the trumpet. And his quote is he wants to be a musicians musician. So I thought it was really interesting. And he’s interviewed two pars an hour and a half and his ideas. The connection to people is very, very important. But if your music career or if your understanding music is somehow steered by the audience with the intention just to simply impress them, to be liked by them, then when they change, your music has to change and therefore you can no longer be you. But that’s very interesting. So I feel like you’re at this really interesting intersection for someone as young as you are. I feel like I’m learning a lot, being ten years older than you are, to know that it’s just as important to connect with people and yet really believe in what you do. And that I always think about it as you need courage to do that.

And sometimes I say this to people that especially when you’re Asian or a Chinese American, you need more courage because you could be in Orange County and even in Boston we’re surrounded by, let’s just say Americans. A lot of the Caucasian population in Boston is still very significant, obviously more significant than Asian population. And the bridal shower I went to was an ex colleague of mine, Helen, and everybody had the bridal showers. It was Asian. I noticed that I started cracking up and you realize just the way that you grew up, and I can’t quite say that because I grew up in Beijing and China there is tremendous amount of pressure in a positive way influenced by the families. They want you to do well. They want you to marry well. They want you to have a really nice job. They don’t worry about any of these things, and they mean really well. But for us, for you in particular, to break out of that pattern and your parents, granted, very supportive, but mentally, there must have been I think it’s more challenging than an average American to really step out and step up to what you’re doing.

Well, I think it’s actually one of the things you touched on. One thing I am very passionate about is Asian American culture. I went to an Irvine Chinese school every Sunday. My parents are very active in the Chinese American museum. My father helped found the New Urban Chinese School, and he’s also a member of the Committee of 100, which is the organization of the leading Chinese Americans in the US. So we’re very passionate about this subject. And he’s also helped a couple of candidates get into office, most recently of which is Ted Liu and Judy Chu. And Judy Chu is the first Chinese American woman in the congress. And it is harder as an Asian American with all these different struggles. I mean, you have the view of old world China, right, which is in Chinese, we have this phrase like only a scholar, only one who studies academics is of the highest peak of society. And then this idea to succeed through scholarship, it’s a good aspiration, but the message in which get you there, that’s where it’s questionable. Right. Long is very famous for having very hard childhood because of the way he was brought up.

He was very stern. It required a lot of physical abuse, mental abuse, and it’s still prolonging in Asia today. Not just China, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore. But we have to start getting away from that. There’s a way to discipline children without resorting to that kind of methodology. But more importantly, as an Asian American in the US. It is you get the struggle of you have to represent your culture. You have to educate people about your culture, and you have to be willing to step out of your comfort zone to fight for your voice. I think that’s really important for my Asian side of being an Asian American. We’re taught to be very restrained. Not submissive, but restrained. I think that’s a viewpoint that a lot of Americans misunderstand. Asians, at least, as Italians and Chinese, we’re taught to be restrained. We’re taught to exercise our mental control over our emotions. When something does not please us, we don’t attack. We reflect. And we reflect on ways how we can improve the situation without resorting to such confrontation. And even though the United States is much better than 40 years ago, there’s still racism. I still face it.

I think we all have had our own share, but we have to find, as you said, that courage to educate people. What it means to be Asian American, what it means to be Chinese or Taiwanese. The nice thing about being in America is you try five minutes is Chinese food, another five minutes is Japanese food, and you can show people your culture. And I think what at least the minorities, I guess an extra responsibility is to show people our culture and to show them that being in this ethnic group and this culture is part of being American. And I think this is especially important this time because there’s a lot of kind of this pushing way of Asia and modern society today, especially in the news. I mean, you pull up any newspaper today and they’ll have a headline saying, asia is the economic enemy. Asia, fill in the blank. And that may make headlines, but you might send the wrong message to other Americans of different ethnic groups. We can’t forget that America is a melting pot, and we are not just one type of people. We’re a group of many people supporting together this wonderful fabric across the country.

So I guess that would be another burden of Asian American, is to find that voice, to find that duty, to share a culture, not be afraid.

We are one. And when I interviewed Matt Linley, who’s a director of innovation, a sapien, there’s one story, and there are many other stories from my podcast. I literally wake up, I think about them. When I go to sleep, I think about them. And one of the stories he said was a true story is looking at Earth from space, and all of a sudden, astronauts are thinking, it’s not them and us anymore, it’s us. And this type of conflict not only happened based on different ethnicities, but even like a marketing agency that I work for. There is a struggle between you’re traditional I’m digital. You work on TV and working on digital campaigns. We are one, and we can just come together, think about how much we can learn from one another. And I noticed one of the things that I feel so spoiled to be living here in the United States, in Boston, and just the fact that you walk down the street and Harvard is an extreme example of this is you literally lock out mass down right now. You could probably meet people from 2025 countries, right? Isn’t it amazing? I mean, even the people who look just like you, they could be from.

A distance, or they could be from I mean, people forget there are 52 ethnicities in China, and I have a lot of friends from Xinjiang, and none of them look Han. It’s funny. I would show my roommates photos of these people and say, hey, this guy’s from China. Well, he looks like he’s a Kurd. I’m like, no, he’s Chinese. You’re right. We’re very lucky. But yeah, I think more of that more of that coming together. That kind of support is a positive influence. And. I believe, with just watching how many more Asian Americans are participating in politics, in nonprofit work, to be active about this education, the world will be a better place. It is, but it will get even better.

Yeah, absolutely. And when you said I love the example. You said, when you stand up on the stage playing the piano or doing anything else, people judge you differently. And in your own people, in this case, if I’m on the audience, I really feel a sense of pride, and I’m just as happy to see people from every ethnicity out there. But when I see Chinese flag in the United States now, very different feeling than when I see the Chinese flag in China, I probably wouldn’t even notice it. And I was listening to this interview. Charlie Rose, I believe. Interviewing chris Rock Chris Rock is my hero. And he said, you know, when I do a movie, when I produce a movie, it’s very different. I’m representing Versus, and it has to be good. It has to be good. If Adam Sandler produces a movie that’s no good, it’s okay. Another week will be another okay, good movie representing white people. But Chris Rapper’s saying that whatever I do, I have to be good, just like Denzel Washington is not just working in the movie. That part is really true, and it’s quite interesting. And I think about this, and I give you this kind of a silly example.

I remember when I was in fifth grade and the story I could never forget. I probably forgot about everything else I learned that year. But my teacher said that on the newspaper in, I think in Milan, but one of the airports in Europe, probably in Italy, that all the signs, messages, welcome in Spanish, welcome in English. And when there was one line for Chinese, it’s like, don’t spit on the floor. And that really hit me, in a way. So I think as soon as I when I arrived in the country, I kept thinking about things like that, and I wanted to behave in a certain way that none that I’ve been on the floor, but I want to try it. I was always very careful. I was raised, in a way, by my grandparents, and my parents were very strict about these things, and they took it to the next level. But I thought, we need to change the image for Chinese people. So back to you. I feel like it’s really incredible what you’re doing, and you’re very humble, and I feel like I can get only so much information about you, your journey, playing the piano.

And you have thousands of fans on Facebook, and every time you post a picture where you’re at an airport and people you’re dropping comments, they’re cheering for you. And thousands of people, many of them are not families and friends, close friends, but they are now they’re supporters. They’re from every ethnicity of our background. So tell us about sort of where have you traveled to and what is the dynamic between you and the people? Because you talk about experience all the time.

Yeah. So one, I guess, philosophy of playing that I really believe in is I, first of all, don’t believe you should ever and as that drummer said, you should never conform your music to some kind of public desire. And what I mean by that is if you can play a beautiful passage at one okay speed. If you can play without playing playing super fast and you’re happy, that’s great. But don’t play it up just to make it a more poppy or something that cheapens the art form that I’m totally against. But what I’m totally for is a style of playing that engages people. And your goal is that when you finish playing doesn’t matter how many mistakes you’ve made because it doesn’t matter how good of a piano player you always make mistakes is that when you finish that concert someone walks away from that and is inspired in some way. And I hope it reminds them, at least of something important in their life that they not just went there to enjoy a piece of entertainment but they went to enjoy the music as a piece of reflection. For me, playing pianos like going to church or wherever your religious places and if you’re not religious, wherever you like to meditate or just to relax.

I want it to be a sanctuary. I want it to be a place where you can laugh, you can cry you can enjoy all the things that we enjoy in life. And I think that’s the most important thing of how to connect with people. And I think when I travel to all of these places when I go to Bali or I go to Puerto Rico or I go to Italy or France or Germany and I play for those audiences I never change the way I play. I have never in my entire life change the way I play. Well, the responses I get are all the same. And I’m very lucky that I’ve been blessed with a communicative ability at the piano. And I will never forget I was playing let’s see, where was I playing this? I was playing in Italy, of all places. And it’s actually at one of Mr. Alexander thessels of Mr. Cosmo Buano from the Alexander Bueno empire. I hope they don’t Harper me for that moment. But I played the heroic Polonnaise by Chopin. And I played that for an Italian audience. In it I thought I’ll never forget. After I played, this old lady came up to me and she spoke in English to me.

She said, I’m actually from Poland, and I lived through World War II. And the way you play Chopin through Poland which Chopin wrote for one of the Polish wars when he was in residency in France. When you played that piece, it reminded me of my time in that war. And that’s all she said, and she nodded and she left. And for me, that was more meaningful than any applause or any accolade after that. For me, that was I was extremely touched by first encouraged to come and tell me this, but my music was able to do that for her. And then I realized, I think I don’t remember how old I was. I think it was like 13 or 14. And I realized, hey, music, this is important. This is a way to touch people. And if I can play this way for someone in Europe, I probably can affect the same way for someone in Asia. And it works. I mean, people are people. It’s not you have to play fast or play in a certain style to make people happy. If you do something that touches them, everyone would feel it. And actually, one thing Mr.

Alexander said that taught me that was very true, and he says, if someone doesn’t like the things you do, that’s fine. There’s enough musicians, they can go on the next track on Spotify. It’s not a big deal. So I guess that’s my answer. My job is to not just provide a source of entertainment, but to touch people. If I touch people, that’s great. And if I wasn’t able to touch them and they didn’t like my music, I’m very sorry. And my role model for this, I guess, would be Yoyo Ma. Many, many classical musicians criticize him for all the artistic interpretations that he decides to do, but they all unanimously cannot disagree on one thing, which is that he is a great communicator. And there’s a reason why he sells out seats at Boston Symphony Hall. It’s not because he’s got the greatest technique. It’s not just because he has a fantastic sound. It’s because when you listen to his music, it’s like looking back at your life and you walk in there and you see 80 year old people walking out crying overjoyed by such wonderful music. And for me, that’s the greatest musician is one who can communicate to people on that level.

You have an obligation, and I don’t mean in a negative way, but this is very positive because I know this is an adorable German Shepherd. I feel like she’s in my life and she’s not my dog, but I feel like we some people on Earth have the mentality of a German Shepherd is that you need something to do. You need an obligation. You’re on duty, and people like you can play the piano the way you do. Not just play, but to feel the way you feel and to enjoy the entire process that you have an obligation to be able to trigger and enable and enlighten. People like myself don’t play the same way. And the funny thing is, for people like us or the old lady that you mentioned in Italy, at all places that they didn’t even know what’s going to trigger that heart. In their hearts, they don’t know what is going to do it. And you know, a lot of the times you walk around in 2015, it’s been going on for 510 years, and everybody you notice on their phone all the time, right?

We’re all guilty of it. I do it too.

So we’re all guilty because many of us cannot, quote unquote, suffer from our own thoughts. Like we cannot be alone by ourselves. Whether you’re on the train, whether people are at my meetings, and thank God, doesn’t happen all that often in other meetings and other venues. I mean, people would pay a significant amount of money to go see a drama, to go see a concert. You look down, you can see a light shining their face. It’s their cell phone turned on. So I think you have an obligation. I love the fact that you’re playing. You’re young and you’re playing and you are I don’t want to say one of the few, but if you look at just the volume of people from X number of years ago compared to people in their twenty s and their teens that are practicing religiously as you do now, I believe a number has possibly been significantly reduced. And I would love to see the number go back up again because my mom, who’s into her early sixty s and just like you, she practiced painting artistry for sake 1012 hours a day. And she is who she is today.

And a lot of these skills, whether it’s piano or art, in her line of work, of restoration and reproduction, they are lost. These skills are lost. They were cared by these masters, and many of them have passed away. And you have an obligation to really pass on that knowledge and at the same time touch people in a way that you didn’t think that you could. I don’t think any of these stories are something that were any of your goals. I would imagine when you’re 19, you made that decision to say, okay, I got boxes to check. Old lady must be completely impressed, must travel to Italy. You didn’t have the set of expectations, but if you knew I could say there could be motivators. But the fact that you persevered through what may be arbitrary or question mark at a time, but only very quickly later on, realize everything’s just blossoming without your goal or expectation of anything, that’s beautiful.

Well, yeah, I mean so just being a student at Harvard makes me a Type A person. That’s unanimous. If you’re here, you’re a Type A person because you worked your butt off.

To get my back.

But one thing we have to forget to try to always do is create that big mega goal and start making small goals. But if you have the intention my mother always said, if you have the intention of doing something well for the good of people rewards will always come. It’s hard to see that immediately. I mean, there’s a reason why we stare at our phones. We love instant gratification. We want to be instantly entertained. We don’t want a time to sink on our own. We don’t want a time to ponder on our thoughts, because it’s terrifying. I mean, come on. Can you think of writing on the subway and you’re sitting down, you’re talking your head, okay, crap. Now I have to talk to myself. When am I going to think about, oh man, that essay I have to write? Am I successful? Man, the other kid just won a Nobel Prize the other day. It’s terrifying because we don’t want to face fear. But fear is what makes us stronger. I feel that the comment about the piano. So actually, factually speaking, there are a lot more people playing piano now. There are 42 million pianists in China, but it’s not rising in the US.

Mind you, it’s rising in Asia. So there’s a joke in the classical music world, you go to a piano competition. First place is Chinese, second place third place is Korean or Chinese. And second place, guys always that one Caucasian guy from America, Russia or Europe, you know, how does that joke? But this is true, it’s decreasing. And there are two countries, the US. And Europe. It’s the less and less pianists. But even with this rise of pianists from Asia, there’s not a rise in the emphasis of playing the piano for the sake of playing the piano. It’s playing the piano for the sake of winning a competition, getting into Juilliard and making money. Making money. Long Long gave a masterclass at the Central District in Beijing, and there’s 3000 people. How many people here think you can be famous for playing piano? Everyone knows there. And he said, this is the problem as a musician, you must play the piano because you love music. And Miukuchi, another very famous pianist, she said in an interview that to be a musician, to be in this profession, is not a career choice. It is a calling. It is something you must do.

That’s the kind of conviction you need to be a musician. And I think that’s forgotten in this hyperpopularized myth that if I be a violinist, I could be the next. It’s a problem. They forget that there are a lot of people in this orchestra that are not inside problems, but there is still in that orchestra every day playing. And the reason is because they love what they do. And so to remove our cap of the salary you want versus what I want as a fulfilled life, I mean, that’s the hardest part, right? That’s the hardest part. To try to differentiate oneself.

In part two of my interview with George, he talks about the business side of things. After founding Four Startups in just one and a half years, I figured that George could share some secret ingredients that contributed to his success today and inspired musicians like himself. At age 22, he has a clear vision of where this journey is going to take him and what he really hopes to accomplish. It is not as simple as just being a musician himself. It is rather a universal message that is going to change music and music education around the world. Find out more in the next episode. Thank you for listening. To listen to more episodes of the.

Phase World podcast, please subscribe on itunes or visit faze world. That is Seism, where you can find show notes, links, other tools and resources. You can also follow me on Twitter at face world.

Until next time, thanks for listening.

Part 2

The Life Of A Pianist, Young Steinway Artist, Harvard Undergrad (Part 2) with George Ko – powered by Happy Scribe

Welcome to the Feisworld Podcast. Engaging conversations that cross the boundaries between business, art and the digital world.

Hi there.

Welcome to the Feisworld podcast. This is your host, Fei Wu. You are now listening to part two of my interview with a brilliant young man whose name is George Co. At age 22, again, so far the youngest guest on my show. George is a pianist, young Steinway artist, and an undergrad at Harvard majoring in music. So in this part of my conversation with George, he starts to talk about the business side of things. After founding four startups in just one and a half years at Harvard, being a freshman and then first half of sophomore year, I figured that George could really share some secret set of skills, the AHA, moments that contributed to his success and perhaps inspire other musicians like himself. I was also surprised to find out that George is so young and someone as young as he is has a clear vision of where his journey is going to take him, what expectation and hope is. So it is not as simple as just being a musician himself. It is rather a universal message that’s going to change music and music education around the world. So how does that happen? During his year off from Harvard, he had the pleasure to conduct a youth orchestra in Orange County, where George is from.

He realized that it is not because that classical music is not cool, it’s not as good as pop music or it’s too difficult to consume, but instead, the truth is we never give it a chance. So he said if I could somehow in my life help bring these programs back, give people a chance, or to just at least open a chapter with a cover of this wonderful book that will be the ultimate goal of my career. So I hope you enjoyed this episode as much as I did. I was simply stunned and reflected so much upon myself my life post producing George’s episode. So I really welcome that you listen to this part as well as part one of our conversation. Find out more in this episode. Thank you so much for listening and please keep in mind there is a blog post associated with these two recordings. Two episodes. You can go to my website. Feisworld, thank you so much for being my audience. Without further ado, please welcome George Co.

We’re now at Harvard University and the name of the building is oh, so.

This is temporary Dunster House. They’re in the midst of their models. So we’re in the Inn at Harvard, which has been converted into a dorm for this year.

Yeah. And this is a piano practice room we’re in right now. And you mentioned that you practice about 6 hours a day.

Three to six, at least three. Ideally, if you can practice 8 hours, that would be great. Some concert pianists claim you can’t practice more than six or four, but for me, I need eight.

No, absolutely. I think this is forget about statistics and averages and all that, right? It’s really a program tailored to yourself. I was interviewing this fitness guru who’s very successful, fitness, of course, illustrated and all that. And his name is Tom Seaborne. And I interviewed him for 2 hours and he said he trains every day, seven days a week. But now, when he’s not in competition and all that, it’s not about performance, it’s not for show, it’s for his personal benefit. It’s an hour a day, he said, but still some experts who say, you’re crazy, your muscles need to rest. And he said, no, it’s not for me. He feels sad.

I know concert pianists who need to practice 2 hours before they perform or they cancel the concert. I know concert pianists that haven’t practiced in two weeks. They show up, they play great, and they have a beer afterwards. I even know some concert pianists have to drink a shot of vodka before they go on the stage.

How do you prepare? How do you prepare yourself?

See, it’s funny. A lot of parents have these rituals. I have no ritual. I just show up. If I can practice, great. If I don’t, that’s too bad. I can still eat before I perform. A lot of people don’t eat before they perform. I don’t really care.

You’re rich, you have to eat.

I have to get my typhoon in for the day. It’s kind of a job. You have to show up, you have to perform well, and it doesn’t matter. I mean, people are not going to care if you’re sick. I remember one time I performed at Carnegie for the Alexander Blood umpire, and I had a fever and I was very tired. But you go on the stage, people can’t know you have a fever. You just walk on, smile, play. Then afterwards, when you’re walking back to the green room, you start coughing. But my belief is it’s a job and you should treat it with some discipline. So, okay, you didn’t practice, you got paid, still go on the stage.

But is it true that when you were playing on that stage for however many minutes, 5 minutes, 20 minutes, did you feel better or did you kind of forget or ignore?

I completely forgot. It’s a task. I mean, Stanford did a study and they discovered that the piano, scientifically speaking, so if there are any violinists listening, they know. I’m not just saying this because I’m a pianist, but it is mentally the most difficult instrument in the world. It requires the most neuron firings that it demands the most of the brain out of all the instruments. And so you become so focused. I mean, even if you had to sneeze, once you start playing the piano and performance, you never think of sneezing again. I mean, you have to be that focused. You’re constantly thinking if you’re playing a passage. Okay, what’s the next part? Okay, I’m going to play this next part. Oh, crud. I’ll make I made a mistake. I’ll fix that later. Don’t worry about it now. Okay. You’re listening so intently and you can hear I always hear of some lady or some man in the audience opening a candy wrapper. It happens all the time.

Do you hear that?

Oh, you hear it? What was I playing? I was playing right here. Even if you’re playing fastpatches.

You can.

Hear it because your job as a.

Performer is to listen.

Right? When you’re playing concerto.

You have to.

Listen to the orchestra. So you’re listening the whole time. You hear people coughing. I heard people snoring asleep. I used to think, oh, man, someone felt they wanted to play badly. But then your mom told me he played one time. His dad slept the whole time. Yo, don’t my dad sleep all the time? Then it’s okay.

Yeah, it’s okay. Oh, my goodness, this is hilarious. I don’t want to make you late for anything. Do you happen to have another 510 minutes? Sure. Yeah. Because I want to get to the business side of things as well. I think you have a very unique set of skills. That sounds like that movie taken. I’m not sure if you sound like a party.

You don’t know who I am, you just don’t know why. But I have a very specific set of skits, and I will find you and I will kill you. Yes. It’s like Liam neeson.

Yes, exactly. Yes. I’ll get to that. No, really have to get to it. But let me two questions before I let you go on your day or practice. I’m sure I’m ready. We are cutting into your practice for sure. It’s all right. Let me take a break. I’ve always loved music my whole life, and I studied how to play the keyboard when I was seven or eight. I remember I was taking lessons for about two years because a neighbor’s son happened to be playing the piano. And I didn’t really stick with it, but I enjoyed it because my parents didn’t push me. Then I started playing Alto Sachs when I was in high school at Freiburg Academy. We had a great music teacher. I had zero experience. I was a senior, but I just wanted to play. And there was not an opportunity in Beijing to play Elto Sachs.

Oh, that’s very true. Yeah.

Yeah. Because jazz music wasn’t as still probably isn’t as popular. It’s more popular now. And I loved it. I loved practicing. But I’m looking at you is because I still practice for those eight to nine months, choose to literally go to the music homes, be on my own while all the other kids were out dating, kissing and all that. I didn’t do any of that. I just wanted to practice. And that definitely touched a music teacher. He walked in one day he was so surprised late at night. One thing I always struggled with, I guess as a result, I didn’t become a better musician. There’s still a chance is I did not memorize the music itself. It was again, I was not born and raised as a musician, and now I’m looking at a stack of paper here in front of me. There’s got to be like 5100 pages of music for one song.

I didn’t bring my concerto, but that’s about 100 pages.

Then you memorize the music. And I noticed this through recording, we’re talking and you’re playing. So I don’t know how to frame that question, to be honest. 100 pages. I know some parts repeat, but for the most part they’re different.

Well, I mean, if you think about it from a mass point of view, it’s possible to memorize because, say, for example, one piece of music, the A two that I always play is Chopin’s A two, number one, which starts.

I.

Mean, it seems like it’s not so bad right now, but that took three years. It’s because the way Chopin wrote this A tude, it stretches and collapses your hand, and it’s one of the most awkward A tubes, and some people can’t even play it. A very famous story is Rubenstein was testing out pianos in Germany, and he was playing this A tude on one of the pianos, and he found out a reporter was recording, and he requested that reporter to delete the recording because he didn’t want people to hear that he was playing that piece. It’s a very hard piece, so some people can do it. I mean, I’ve seen twelve year olds play it, but then there are some people who never touch the piece in their lives. So when you work that hard on the piece, I mean, you memorize it because of the muscle memory in your fingers. By looking at the score so many times. If I’m thinking of, let’s say, a shopping piece I’m working on on the 6th page, it will be you just know because you’ve looked at the score so many times. So memorization is inevitable because of I mean, what might be fun for the podcast is people don’t know how pianists practice.

And so, for example, if I play this one passage to just play that little short thing, I would have to do all these different dotted rhythm practices like or and then just do the top parts of my so much, you have to do just for four measures of music that could be anywhere from two to 20 hours of work.

Wow.

And so when you put all of that time together, you’re able to memorize a piece because you spent a good one month to two years on it.

That reminds me of Malcolm Gladwell’s. Ally, 10,000 hours. What do you think of 10,000 hours? Do you even think about it in terms of practice hours?

I did during my year off when I started because I did the math. Because I did math. I took linear algebra and differential equations at Harvard.

Oh, I did, too.

Okay, math. I stopped after that because the next math class I took, the average IQ was 150, and I said goodbye, but I did the math. And up until my year off, I only practiced almost three 0 hour. I was not even close. And so I started looking at pianists who didn’t have the luxury at that time. And mind you, actually the real number of hours of concert pianists that have practiced to reach the level, like, say, long. Long is more like 19 to 25,000 hours. So Malcolm Gladwell’s might work for hockey, but it doesn’t work for musicians. And mainly because you have to practice so much that you would ingrain habits into your own body by will. And that is something you can’t just even $10,000 is a lot, but I don’t think that could do it, even that amount. So I started looking at pianists who practiced differently, and there’s one pianist in particular, arcade Velodos, he was an opera singer. Then at 17, he said to his dad, I don’t want to be an opera singing anymore, I want to be a pianist. And he has the most legendary technique today. But he started when he was 17, so how did he practice?

Well, he was very efficient. He would never play piece through when he practiced, he would just play what he needed to work on. He would always play charity, he would always work on technique, and once something was wrong, he stopped immediately and fix it. And so that’s what I did. I tried to change the way I practiced.

I’m so glad you brought this up, because I’ve been a martial artist for about 14 years now.

Oh, wow. What’s your style?

When I was a kid, it’s probably more than 14 years, but when I was in China, I practiced kung fu, I was very spoiled.

Which style of kung fu?

There is a young style, and some of that these days is intertwined with Tai chi, but there’s a wu style, there’s a young style, and honestly, for me, it was a hodge project. It wasn’t quite official, but for the past what about you?

Yeah, I studied Ching, Senpai and Susan. So the chimpanpai is the Dallas version of tai chi. And then my father was a martial artist. He had six black belts, so he taught me. I was actually more specialized in Chinese grappling.

Wow.

So then I haven’t practiced in a couple of years.

It’ll be awesome if I throw you over the piano right now and slam.

Yeah, we could spar on doing an interview. That’d be interesting to close the interview. Right, but that’s interesting. So you studied mushrooms for 14 years?

The past 14 years, 1314 years was very focused on taekwondo. And the funny thing is, my uncle did not approve, not that I really cared, but he said, You’re Chinese. Why are you practicing taekwondo? And I said we are one, remember? The thing was, as soon as I got my yellow stripe, just a few months in, I was practicing every day, like the way you were with piano, completely obsessed. And I ran, and I got my yellow stripe, and my uncle was trying to attack me. I was 1718 years old. And he said, I’m sure you don’t know what you’re doing. You’re just a yellow stripe. And he was right, and he’s trying to throw a punch at me for fun. And all I did, I picked up my knee at just one of my knees, and he punched right into my knee and broke his little pinky finger.

Oh.

I know this is a story I haven’t told him about podcast yet, but I recently got my third degree white belt, and congratulations. Thank you. And it’s very special, even though just by number, that’s not really I’m not just going for the ranks. But what you said just now about your practice, it was so interesting, because that’s exactly how I was taught or how we practiced the forms. As you know, in tai chi forms, sometimes there are 100 and 2150 moves, just like your music, whereas in Taekwondo, the more sophisticated forms or it could be honestly, I haven’t counted. It could be maybe like 50, 60, 70, right? And typically, it’s not over 100, but it’s so fascinating. My instructor, Mr. O’Malley, I watched him practice his forms, and the way he taught me was he watches me. He’s like, stop. You always start from the beginning to finish, right? And if you watch anyone, the second half of their forms are significantly less well constructed than the first half. They’re tired, and they’re always in the middle. When it comes to tricky. With Taekwondo, you could do a turning, flying sidekick, and there’s a wheel kick, the form of working on MooMoo.

It’s very advanced, but instead of just throw a psychic in the air, you got to hold it there. You got to turn with 1ft. So you need flexibility, but also sort of stamina and strength. And you typically have one or not both. But either way, the power of breaking down the form or your music to practice visually, it is so powerful. Anyway, I cannot stop and start talking about Taekwondo, and we’ll break into, like, 10th episode, but we’ve been talking for a while. This is fascinating. I want to thank you because one of my dreams was to say, one day, when I have enough money you know what? That’s actually a wrong excuse. I want to be able to travel around the world, but not just travel. I want to experience every profession out there. I could probably do that in the US. It’s a big country, and my dream is to sit down for one day or possibly one or two weeks to sit down with a piano player, with a basketball player, with out of the sports role, a martial artist or a marketer advertiser, whatever that may be, and just experience, like, what they do, how they practice, and when do they put on a show, and it’s awesome.

But before we close the podcast, I wanted to ask a sort of business related question, which is, I feel like at some point, especially musicians or artists, to say, look, I’m going to have a family as a man or a woman. Right. Look, I’m not saying I need $10 million or anything extravagant, but I need to be able to get by, right? And recently I really opened that up because working in advertising myself, my mind is filled with all these opportunities, a way to market yourself. My mom’s an artist. She’s like, I hate that. She’s like, I hate marketing. I hate marketing myself. Right.

Everything’s about your work, right? There is this thinking that if you’re the artist, you just have to work on your art form and somebody will hold your hand and walk you through. But the thing is, all the most successful musicians, this was never the case. Now, I have to admit, there is some element of luck. There always is, but that’s not always the case. People forget that Beethoven, when he premiered the 9th Symphony, he had to knock on a lot. Yeah, he was deaf at this point, completely deaf. He had to knock on a lot of people’s doors just to get music stands for the musicians. He had to find bows for the violinist. He organized the entire concert by himself. Probably the most important symphony in classical music history was done by a man who was very entrepreneurial in that sense. Many of these classical grades had to find ways to support themselves. I mean, Chopin, for instance, made a living not through his compositions. He made a living through teaching. And he had a very, very, very prestigious teaching studio. And he created a demand that allowed him to charge a very exorbitant rate to support his living.

And so we forget as artists that, hey, they’re great artists, but they also had that same thing, I have to have a family. I want to make a living. I don’t want to be poor. So I guess the advice for today is treat your career as an entrepreneurship endeavor. And don’t once think that just because you’re not performing at Carnegie Hall or at Lincoln Center that you’re a failure. That’s not true. The real failure is if you’re not doing anything and you find ways to get a career going. There’s a lot of artists that make fun of Longlong, for instance, because they call him a cell out. He does all these commercials. He does all this stuff for Mont Blanc or Audi. But let’s face the facts. He makes a couple, I think they estimated 20 million a year. He has an extravagant lifestyle. He is on the pop media, he plays in the Beijing Olympic opening ceremony, but he does all of that to get his name out there. But then when he records a CD or he plays at a prestigious concert hall, he is a serious musician. Right? You have to wear different hats.

And I’m not saying you have to wear different hats to be like twoface Harvey from Batman, but you have to wear different hats to find your niche, right? Because, like an advertisement, right, you need to hit a certain demographic. You need to sell them a product. For example, you need to sell a car that’s geared towards college graduates in Boston from the ages of 22 to 27. And so you need to figure out, well, what can I do to make them want to buy this car? That’s what you have to do as a musician. I’m not saying you should do that with your music, but you should do that with the way you market yourself as a brand, as a product. So even though, yeah, the average salary of a musician in the United States is $23,000 a year, it’s absurdly low. But if you’re smart and you work hard and you treat yourself as an entrepreneur instead of just an artist, a lot of opportunities started opening up. And that’s the advice, actually, Mr Alexander and Mr Boomitz gave me, and they actually have this wonderful book. And if you’re listening and you are an aspiring musician, you should at least give it a look.

It’s called The Classical Musician Today and that book really asks these hard questions, but it guides you in a way, to think of your career more as an entrepreneur, as a Mark Zuckerberg, rather than as just a young daily. Just a musician.

You have a very visible and very well done internet presence of you and meaning the places I’ve looked so far. Your website is very professionally done. Thank you. I like it. I’m not saying it doesn’t need to be perfect. That’s not the idea for people out.

There to make anything perfect.

Exactly. Even as musicians, get something out there convincing the audience to get something up and running. And don’t be embarrassed by it. If you feel embarrassed, go to a very smart professor’s website. Any university professor have decided unanimously that they do not need anything other than eight simple, straight up HTML. You probably noticed that, but your Facebook fans and you’re probably on Twitter. I haven’t looked.

Yeah, I’m on Twitter.

Where else? Or are you on? Just kind of give our audience a way to follow you and to know how you conduct your business.

Right? So I’m on Facebook. Facebook.com Georgetcomusic. My website is Georgecopiano.com. I’m on YouTube. Youtube.com, Georgecopiano. I’m also on Twitter at Georgetco piano and I’m also on LinkedIn. So those are my main social networks. I’m probably going to start Instagram soon, just because I love taking pictures of food and I actually have a food blog just for fun. It’s called co kitchen. So you can go to Cokitchen.com. And I like to cook, so I post photos of what I like to cook. It’s just a little fun thing. But yeah. So actually, with all the web presence, speaking as an entrepreneur, I did all of that on my own. I didn’t hire anyone to do it for me. And I actually worked I interned at an ad agency in high school called Superfad, and I helped create a commercials for Coca Cola Sprites. So I got to see that kind of the world. And with the background in training my father gave me through his business, I was able to kind of piece everything together. And I have a brother who’s a Whiz at Computer Science and Engineering, and he’s also at Harvard.

Wow.

Is he younger or he’s younger and brighter and yeah, he’s in Adam’s house since I took gear off. We’re now both juniors, and so we’re going to graduate the same time. That’s great. He’s my best friend and so it’ll be fun. But yeah. So he helped me with some of the coding and yeah, I really just did everything on my own.

I love where you’re going with this, because so many people out there think it’s an excuse that I’m not a computer scientist, I’m not a mathematician. I cannot do this. You can always do this. There is no better error than now to do all of these things.

Yeah. And I think actually what I’m just.

Saying, even with the smartphone, you can take pictures, you can advertise yourself, share your ideas.

Yeah. So for some of the recordings, I’ve done it myself. I have a pull tool system at home. I was also very lucky. I was trained by a recording engineer, nico Bolas at Capital Records. And so he taught me how to make a piano. And you can go on Amazon right now, buy a Zoom H four N for $220, and get a pretty decent recording of yourself. All of the photos on my website were done by myself. It can be done. And there’s thousands and millions of tutorials on YouTube how to build a website. You can go on it sounds like I’m plugging for products right now, but there’s a great website coming called Squarespace, and it’s completely drag and drop. Just drag and drop everything. And you can build a website. I did everything on WordPress just because there’s a template I liked, and then I designed my own code. Yeah, I mean, there’s just a bunch of free services that you can do. It’s so easy to get a website. Now. Just go on. GoDaddy. Actually, don’t go on GoDaddy now. Go on Google. Google has a new domain site and you can buy a website, set it up in less than I built my website in about 3 hours.

Anyone can do it. You’re absolutely right. And I think this is the perfect time, actually, to be a musician, because there’s so many things you can do and think of ways to change the way you perform. Like, I’m working on a project to perform hopefully at either a car dealership or I’m a big fan of Leica. One of my things is I like to perform at a Leica store. And fortunately, as a Steinway artist, I can have Steinway Sunday piano and you can do an event for Steinway and Leica, but play some classical music. So think of ways to get your music out there. And it doesn’t always have to be at a concert hall.

So true. It could be on YouTube. I mean, all these opportunities are going to broadcast yourself, like what we’re doing right now. It’s really amazing. And especially, I think, piano music in general, it’s really good for podcasting, and you can talk about your music, share your emotions, and I love what you did, bits and pieces, and really added a significant dimension to the podcast. Instead of just two people talking back and forth with one another. It’s really amazing. So, wow. What’s your next steps? What do you want to do, like, say, ten years from now? Is it playing, supporting, coaching other musicians? Or what does that trajectory look right now?

Actually, I wrote this in my college essay to Harvard. There is a decline in classical music. It’s very sad. In this country, there are less people going to the concert halls. When you walk into Boston Symphony Hall, the average age is 60. It’s very real. And progressively, in 20 years, there’ll be no audience. So what are you going to do? I’m a costco musician. I don’t want to play for no one. I mean, unfortunately, the reality is I do need to make a living. I need to put food on the table. But more importantly, we’re going to lose this appreciation for this wonderful art form. So my dream is to work with the US government and the White House to create a task force to help reinstitute all the music appreciation programs in every public school in this country. And in the 50s, there was a music appreciation class in all these schools. And those are the people that are sitting in the audiences today, the people that benefited from this wonderful public education system that has now just been crippled with bad debt, unnecessary resources and spending. These schools have to cut all their artistic programs just to get teachers to come teach not even five classes a day.

And so I would love to work with the government to see if there’s a way we can get these programs back, get these artistic teachers back, inspire these children to keep playing their instruments and to sponsor local orchestras and community orchestras that these students can perform in and show them that this is music worth looking at. This is music worth playing and enjoying. So I guess. Conducted a youth orchestra during my year off in Orange County, and I was asked to conduct a bunch of first to fifth graders. And can you imagine? You have to try to inspire the most energetic group of people in the entire world to play slow music. Slow music. I mean, we were playing Ravell.

But.

I treated it as a way of accomplishing something. And when we played the piece and we finally perform, every child had a smile on their face, and they were so excited, and they were so pumped to practice, to do the next big show. And then I realized something. It’s not classical music is boring or it’s dead or it’s not interesting or pop music is easier to consume. It’s just we never gave it a chance. That’s really what it is. And so if I can, in some way in my life help bring these programs back, to help give people a chance to at least open the cover of this wonderful book, that would be the ultimate goal for my career.

You’ll be the next Jamie Oliver. You like cooking? You must know who he is. Yeah, he brought fresh food to local schools, and there’s so much what he does that I love. But what you’re doing, it’s almost more significant. I mean, it’s just as significant, you know, it’s really incredibles. And I feel very blessed to have you on my show.

It’s my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Thank you. It was so much fun. And really best of luck to all your endeavors. And keep me posted. Keep us posted.

Absolutely.

Yeah. And see how it goes. And it’ll be awesome to have a follow up to this as well.

Absolutely.

Thank you.

To listen to more episodes of the.

Faith World podcast, please subscribe on itunes or visit feisworld.com that is Seif, where you can find show notes, links, other tools and resources.

You can also follow me on Twitter at space world. Until next time, thanks for listening.

Word Cloud, Keywords and Insights From Podintelligence

What is PodIntelligence?